What is Antifragility in Education?

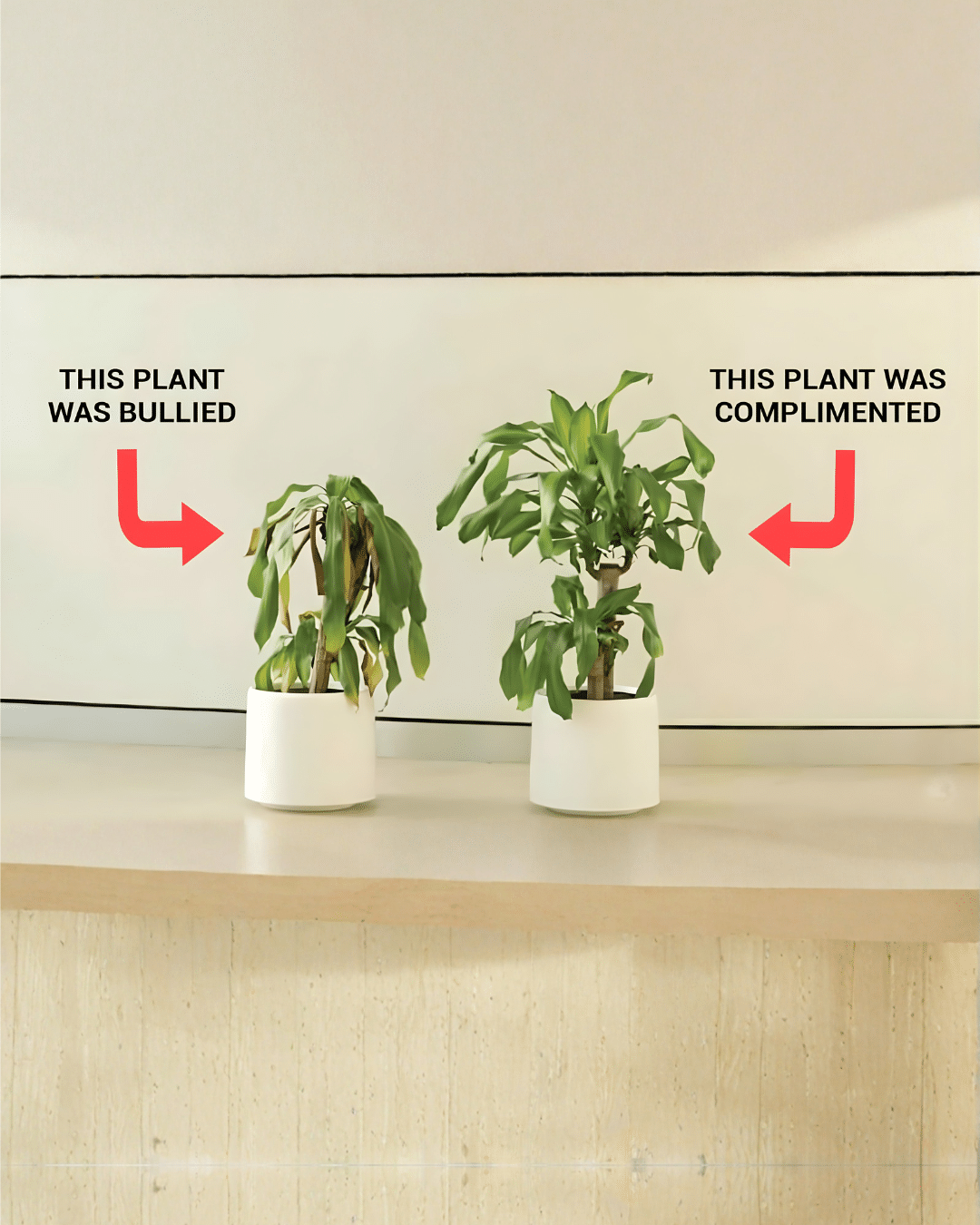

🥛 Imagine you drop a glass cup. It shatters because it is fragile.

🪨 Now think about a rock. If you drop it, nothing happens. The rock is considered robust because it can handle stress. However, it does not grow from the ordeal.

💪🏼 What about muscles? When you exercise, your muscles experience stress and small tears. But over time, they grow back stronger.

That is antifragility: becoming stronger and better through stress and challenges.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of Antifragile, explains that in a world full of uncertainty and change, we should not just try to avoid stress or failure.

This is especially true in today’s rapidly evolving education landscape in Malaysia. Preparing the new generation for an uncertain future is more important than ever. That’s why, instead of avoidance, we should strive to create environments where students can grow stronger when faced with challenges.

At Fairview International School, this principle is embedded across all levels of the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum, from primary education in Malaysia to secondary years and beyond.

How to Build Antifragility in Primary and Secondary Education in Malaysia

In schools, educators often try to shield students from failure and stress.

However, too much and it becomes overprotection, which in turn makes them even more fragile. If students are not exposed to challenges, they will not know how to handle setbacks when they happen in real life.

The key is to introduce manageable stressors that promote growth while providing a safe and supportive environment.

Whether in private primary schools, secondary schools, or international schools in Malaysia, building antifragile learners is increasingly a priority. Many of the best international schools, including Fairview, are embracing inquiry-based models that encourage critical thinking and emotional resilience.

Here are three powerful strategies to make students antifragile:

1. Embrace “Via Negativa” (Learning Through Subtraction)

“Via negativa” means improving by removing what is holding you back instead of adding more.

In education, this means identifying and removing barriers to learning rather than just providing more resources or support.

This strategy is especially relevant in both primary and secondary years, where resilience and initiative are foundational.

How It Works:

- Letting students struggle a little before helping them. Let them try to solve their problems on their own.

- Reducing overprotection. Let students face the natural consequences of their actions within safe limits.

- Limiting excessive rules and structure to encourage creativity and independent thinking.

Examples:

- A private primary school teacher might introduce a new math problem and let students figure out the solution first before teaching them the correct formula.

- In a private secondary school, a science project may be given with minimal instructions to students to experiment and problem-solve on their own.

Why It Works:

- Research shows that problem-based learning improves critical thinking skills by 20% (Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007).

- Students who face controlled challenges are better able to adapt and solve problems independently (Loyens et al., 2008).

2. Introduce “Good” Stressors and Controlled Challenges

Just as lifting weights makes muscles stronger, facing manageable challenges helps students develop resilience and confidence.

These strategies lay a strong foundation in primary education and become especially impactful during the secondary years in Malaysia.

How It Works:

- Using problem-based learning where students work through real-world problems with no single correct answer.

- Encouraging debates and discussions to expose students to different perspectives.

- Including open-ended projects where failure is possible and acceptable.

Examples:

- An elementary school teacher might give students different materials and ask them to build the tallest tower possible.

- In the Middle Years Programme or high schools, a teacher might assign students a research project on a controversial historical event that requires them to present multiple perspectives.

Why It Works:

- A study found that problem-based learning increased problem-solving ability by 30% (Susanti et al., 2023).

- Students exposed to moderate levels of challenge developed greater confidence and adaptability (Loyens et al., 2008).

3. Cultivate Optionality and Redundancy

Optionality means having multiple paths to success, while redundancy refers to having reliable backup plans. Both are vital for building antifragility, giving students the flexibility and security to navigate uncertainty by reducing the fear of failure and taking thoughtful risks.

How It Works:

- Encouraging students to develop diverse skills, including communication, problem-solving, and creativity.

- Teaching students to self-reflect and adjust their learning strategies.

- Allowing students to experiment and explore different approaches to solving problems.

Examples:

- A primary school teacher might let students try multiple methods to solve a math problem.

- Students in the Middle Years Programme may be asked to present their learning through video, art, or essays. This gives them options to demonstrate their understanding of the subject matter via different channels..

Why It Works:

- Studies show that students who develop a broader range of skills are more adaptable in a rapidly changing world (Ybarra, 2023).

- Developing metacognitive skills improves students’ ability to monitor and adjust their own learning strategies (Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007).

Together, these strategies equip learners to face complexity, ambiguity, and adversity with courage and confidence rather than fear. They provide a holistic framework that develops strength from challenge, preparing students for lifelong growth.

How to Start Tomorrow

- Let students struggle before offering help.

- Introduce meaningful challenges through problem-based learning and open-ended projects.

- Encourage students to develop a wide range of skills.

- Create a classroom culture where mistakes are seen as learning opportunities.

- Choose a school that offers internationally recognised programmes like the IB to support resilience and future-ready skills.

Fairview is regarded as one of Malaysia’s best international schools that offers a complete IB education. It embeds antifragile principles from the Primary Years Programme to the Middle Years Programme and beyond, cultivating resilience, adaptability, and independent thinking throughout the learning journey.

What is the International Baccalaureate?The International Baccalaureate (IB) is a globally recognised curriculum that fosters academic excellence and holistic development. It comprises:

Fairview International School’s IB programme supports the development of learners at every stage. With a focus on inquiry, reflection, and international-mindedness that aligns closely with antifragile principles, students are prepared to adapt, overcome, and thrive in a world of change. |

Final Thoughts

A fragile student breaks under pressure.

A robust student can handle pressure, but does not grow.

An antifragile student becomes stronger, more confident, and more adaptable with every challenge.

These are the kind of students we want to raise

Families looking for future-ready learners should consider schools that embody these values. At Fairview, students are not just prepared for exams—they’re prepared for life.

Ready to help your child grow stronger through challenges? Reach out to us today to learn more about Fairview’s IB programmes and how we nurture antifragile learners for tomorrow’s world.

Works Cited

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2007). Scaffolding and Achievement in Problem-Based and Inquiry Learning: A Response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006). Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99–107.

- Loyens, S. M. M., Magda, J., & Rikers, R. M. J. P. (2008). Self-Directed Learning in Problem-Based Learning and Its Relationships with Self-Regulated Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 411-427.

- Susanti, M., Suyanto, S., Jailani, J., & Retnawati, H. (2023). Problem-Based Learning for Improving Problem-Solving Skills. Journal of Education and Learning, 17(4), 506-514.

- Ybarra, O. (2023). Teaching the One Skill Employers Desire Most. AACSB Insights.