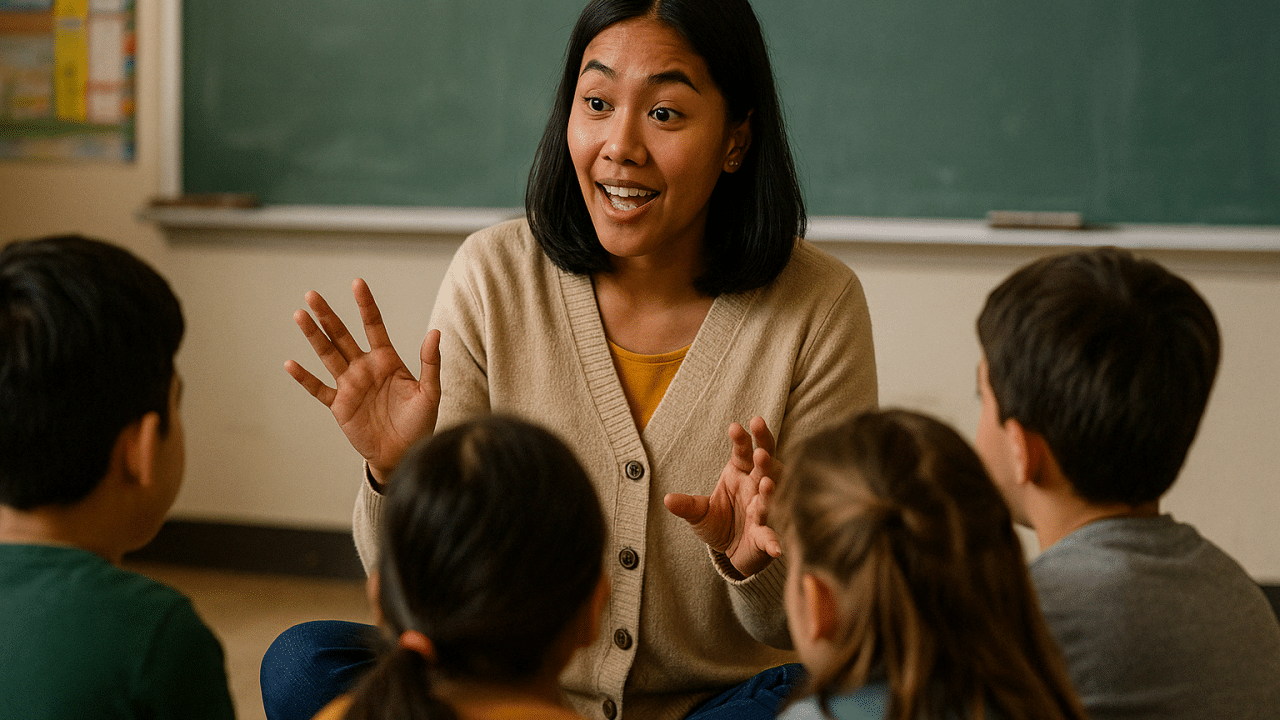

In a small Year 5 classroom in Malaysia, Felicia stood in front of her students. Not with a worksheet, but with a story.

It was about a village where water was scarce. Two brothers, one selfish and one selfless, had to decide whether to hoard or share their well.

The students were captivated. But more than that, they were thinking.

“Why did the selfish brother feel justified?” one asked.

“What happens when one part of a system takes more than it gives?” another pondered.

Felicia smiled. They were right where she wanted them.

This is a familiar scene at Fairview, a leading international school in inquiry-based learning from early years to high school in Malaysia.

The Real Challenge of Concept-Based Teaching

Concept-Based Curriculum, or CBC, is a powerful approach, but it is notoriously hard to get right.

Instead of focusing on memorising facts, CBC helps students understand big ideas like interdependence, systems, responsibility, culture, and equity. These concepts are designed to transfer across subjects and real-life situations. The goal is deeper thinking, not just knowledge recall.

But here’s the challenge. Most educators were trained to teach content, not concepts.

And concepts, by nature, are abstract. You can’t point to “systems” or “identity” on a worksheet. Without a strategy to make those ideas concrete, teachers often fall back on surface-level activities.

The lesson risks becoming confusing, dry, or disconnected.

That’s where storytelling comes in. It offers the missing bridge between the abstract and the personal.

Whether it’s in a primary school classroom or within the Middle Years Programme in Malaysia, concept-based learning, when grounded in relatable strategies like storytelling, encourages deeper understanding across disciplines.

1. Storytelling Makes Abstract Ideas Concrete and Memorable

“Systems” might sound vague on paper.

However, when Felicia told the story about the village and the well, her students felt the consequences of imbalance. They didn’t just learn a definition. They saw how parts of a system interact, and what happens when one part fails.

This isn’t just feel-good teaching. It’s backed by science.

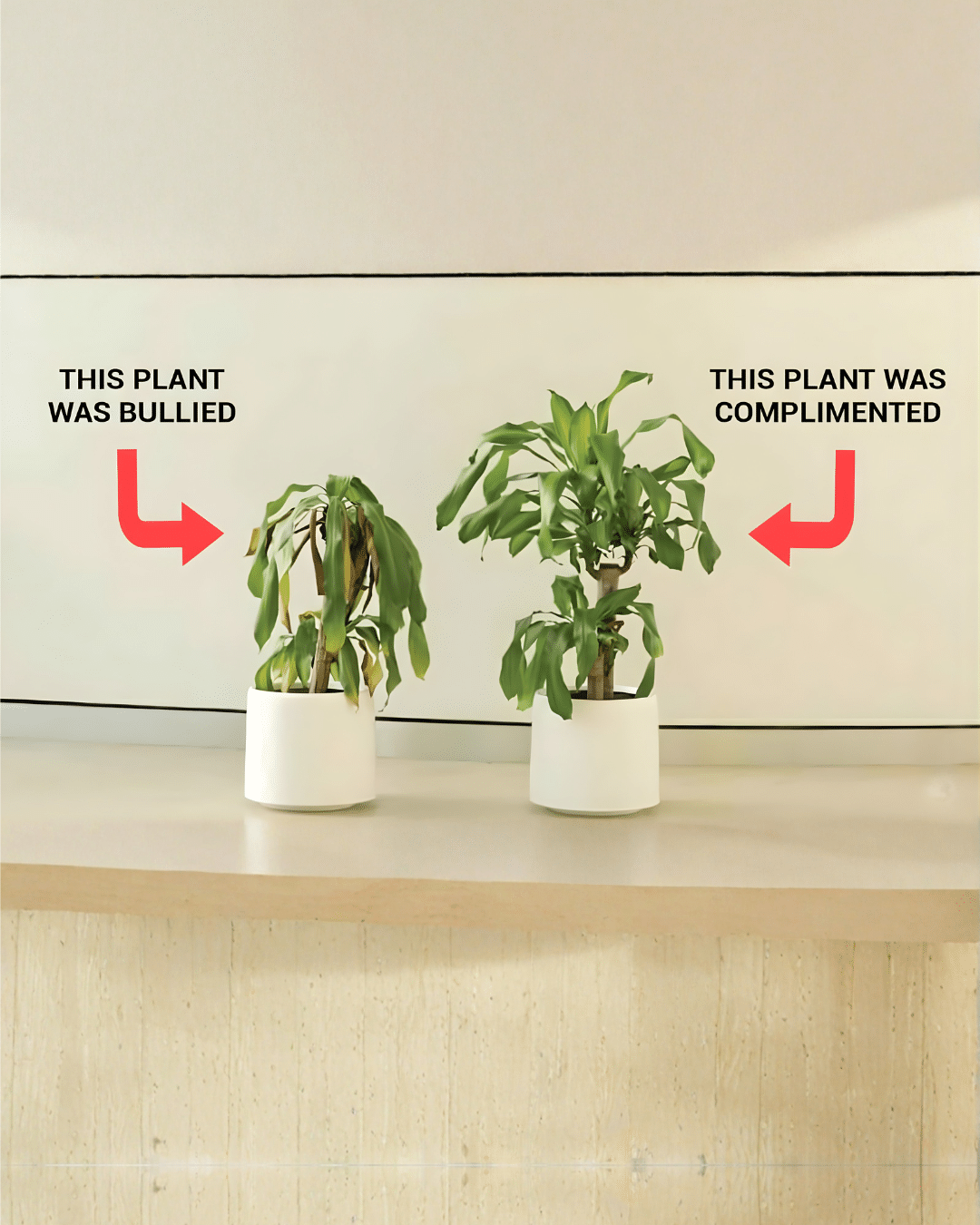

Cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner argued that facts embedded in stories are far more memorable than standalone information. Some studies suggest students remember content up to 22 times better when it’s presented in narrative form.

Neuroscientific research by James McGaugh further supports this. Emotional engagement activates the brain’s memory systems, helping students store what they’ve learned in long-term memory.

In short, stories help students remember what matters.

As such, for younger learners in a primary school in Malaysia, abstract ideas like “systems” are best understood through emotional, relatable stories.

2. Stories Create Empathy and Global Awareness

The next day, Felicia shared a story about a refugee girl escaping conflict. When the story ended, the classroom fell silent.

“I never thought about how scared she must’ve been,” one student whispered.

That single moment was more powerful than a slideshow on human rights. Because the story didn’t just inform. It invited students to feel.

In the Middle Years Programme and across top secondary schools in Malaysia, storytelling fosters not just knowledge, but also human connection and empathy.

Empathy is essential in today’s global society.

Studies show that reading or listening to character-driven stories improves Theory of Mind, which refers to the ability to understand another person’s thoughts and feelings. One study found that even brief exposure to fiction can enhance empathy and reduce bias.

In a CBC classroom, this matters. Concepts like culture, identity, and bias are not meant to be memorised. They are meant to be explored with depth and care.

Stories help students walk in someone else’s shoes, even if just for a few minutes.

3. Stories Integrate Subjects and Skills Seamlessly

On Friday, Felicia told her class a story about a boy who built a windmill to save his drought-stricken village.

That single story led the class to investigate renewable energy in science.

They mapped wind patterns in geography. They debated ethical questions in citizenship education. They wrote persuasive letters in English. And they collaborated on a design project to build their own windmill models.

Felicia didn’t need separate lesson plans for each subject. The story created a shared context for integrated learning.

Cognitive neuroscience supports this too. When we hear stories, our brains engage language centres, visual imagery, emotional processing, and even motor planning. This rich, whole-brain engagement mirrors how we use knowledge in the real world, not just in silos.

The story made learning feel alive, relevant, and connected—an approach fully embraced at Fairview, where the IB journey from early years to high school in Malaysia fosters seamless, interdisciplinary thinking at every stage.

Why This Matters Now

Felicia’s true gift is not that she tells stories. It’s that she knows when and why to tell them.

She understands that Concept-Based Curriculum is not about checking off content. It’s about building thinkers. And she knows that stories are the most human and effective tool to help students understand, remember, and apply complex ideas.

In a world full of information, facts alone are not enough.

What students need are powerful, transferable concepts and meaningful ways to connect with them.

That’s why Felicia doesn’t just teach with stories. She teaches through them. And her students don’t just remember what they learned. They understand why it matters.

Similarly, at Fairview, a leading name among schools internationally, storytelling is not just a teaching tool. It’s a bridge to deeper understanding.

Interested in how storytelling can transform your child’s education? Contact Fairview today to learn more.

Works Cited

- Bruner, Jerome. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Harvard University Press, 1986.

- Kidd, David Comer, and Emanuele Castano. “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind.” Science, vol. 342, no. 6156, 2013, pp. 377–80. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918.

- McGaugh, James L. “Memory—A Century of Consolidation.” Science, vol. 287, no. 5451, 2000, pp. 248–51. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.287.5451.248.

- Speer, Nicole K., et al. “Reading Stories Activates Neural Representations of Visual and Motor Experiences.” Psychological Science, vol. 20, no. 8, 2009, pp. 989–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02397.x.